“Keep it simple” is a fine idea that reduces to a cliché when used, well, too simply. Without enough reflection, the imperative phrase becomes useless, even destructive. Given today’s complex environments, “keep it simple” appears to be the clarion call every team needs to stay out of trouble. Alas, the opposite is likely true unless we recognize the system dynamics in our ways of working.

Recently, I stumbled upon Ashby’s law again on the very day when a colleague admonished us to keep a situation simple. The colleague’s appeal was well intentioned, even wise in the sense of avoiding doing too much. I was nevertheless troubled by what felt like a dismissal of the conceptual work needed to confront the complexity of our project.

All organizations are complex systems because they are composed of human beings. As they grow larger, the complexity expands exponentially to become effectively infinite. Furthermore, every organization is participating in a complex web of social institutions and markets. This situation distinguishes modern societies from pre-modern ones, where the daily experience of most individuals consisted of farming dawn-to-dusk to scape our an existence from the land.

Ashby, among others working in this field such as Stafford Beer, conceived of three main elements that compose or influence any self-organizing system:

If we are faced, however, with a highly various environment, simplification can be dangerous. We see, for example, in individual thought how heuristics play enable us to decide quickly. But, at least since Daniel Kahneman’s work, we know how flawed our heuristics (availability bias, optimism bias etc.) are. Kahneman states it simply: As necessary as the heuristics of “thinking fast” are for our survival in flight-fight situations, more “thinking slow” would do us good. “Keep it simple” is for me often just too fast a response.

As we saw above, we distinguish complicated and complex based on our knowledge. In the context of Ashby’s law, we can perhaps put keeping it simple on firmer ground. So, let’s examine some good and bad ways to simplify.

It cannot be stressed enough that “keeping it simple” is often harder conceptually than diving down the rabbit hole of details. It requires experience with the problem domains to recognize what is important. It requires tested heuristics to ensure completeness of scope. And, it requires hypothesis testing as a tool to uncover unwarranted assumptions early on. But, with a little discipline and a little practice, such techniques are neither hard nor costly.

Recently, I stumbled upon Ashby’s law again on the very day when a colleague admonished us to keep a situation simple. The colleague’s appeal was well intentioned, even wise in the sense of avoiding doing too much. I was nevertheless troubled by what felt like a dismissal of the conceptual work needed to confront the complexity of our project.

Ashby’s law

Ashby’s law says “variety absorbs variety”./1/ Otherwise stated, “Systems must have a variety of control mechanisms that are at least equal to the number of potential disturbances/challenges that the system must face.” Ashby defined variety as the number of states in system. Without sufficient variety of controls to managed those states, “the environment will dominate and destroy the system.” A city center without enough traffic lights and roundabouts engineered for the traffic dynamics will result in gridlock once the volume exceeds the capacity.All organizations are complex systems because they are composed of human beings. As they grow larger, the complexity expands exponentially to become effectively infinite. Furthermore, every organization is participating in a complex web of social institutions and markets. This situation distinguishes modern societies from pre-modern ones, where the daily experience of most individuals consisted of farming dawn-to-dusk to scape our an existence from the land.

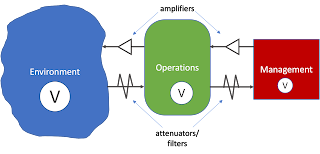

Ashby, among others working in this field such as Stafford Beer, conceived of three main elements that compose or influence any self-organizing system:

- Operations: elements which do things.

- Management: elements which control operations.

- Environment: the surroundings within which the other elements function.

Nevertheless, Ashby’s basic message was: we cannot escape the complexity born of variety, we can only meet it with a commensurate level of variety. In human organizations, this frequently means retaining sufficient flexibility or harnessing the wisdom, i.e. the variety in the group’s experience./2/ Indeed, organizations themselves are institutions whose social purpose is to reduce environmental complexity (by leveraging the use of operations and management).

Cynefin

In addition to Ashby’s law, the cynefin model has provided useful distinctions between simple/obvious, complicated, complex and chaotic.- simple/obvious: straight forward cause-effect models that allow easy quick decisions according to best practice.

- complicated: intricate systems with lots of parts, whose cause and effect is nevertheless knowable by experts.

- complex: intricate systems, whose elements and relationships exceeds our knowledge and ability to predict the outcomes. We gain understanding and management through statistics and probabilities. We must act in a states of uncertainty. Human organizations, social institutions and markets fall in this category.

- chaotic: no detectable cause and effect relationships.

Keeping things simple vs. being stupid

With this background, let’s review what “keep it simple” means. The appeal to “KIS(S)” is heard in complex and sometimes in complicated situations. The message: don’t get bogged down in the details, don’t waste time on unnecessary elements, don’t increase the number of elements we need to manage etc. These are indisputably worthy goals.If we are faced, however, with a highly various environment, simplification can be dangerous. We see, for example, in individual thought how heuristics play enable us to decide quickly. But, at least since Daniel Kahneman’s work, we know how flawed our heuristics (availability bias, optimism bias etc.) are. Kahneman states it simply: As necessary as the heuristics of “thinking fast” are for our survival in flight-fight situations, more “thinking slow” would do us good. “Keep it simple” is for me often just too fast a response.

As we saw above, we distinguish complicated and complex based on our knowledge. In the context of Ashby’s law, we can perhaps put keeping it simple on firmer ground. So, let’s examine some good and bad ways to simplify.

Simplification possibilities

- Elevation to principles reduces variety by reducing the decision case to an adherence to a principle, thus amplifying the management regulatory power while filtering the details in the lower domain (usually operations). Many regulations imposed by management work in this way. And, still, the number of exemptions from the rule sought by operations demonstrates how the variety within the system seeks to exert itself. It hasn’t gone away, but the control variety is strong enough. Within the “KIS” framework, such a mechanism might be a rule for new product proposals requiring the statement of the customer’s value proposition in one sentence.

- Exclusion of detail entails a filtering out of facts known by experience to be unimportant for the decision. Of course, we cannot be absolutely certain that we haven’t excluded something important. But, sufficient experience usually. A simple example is a manager deciding based on rounded numbers: if it’s 1.3 million, we scarcely need to know that it was precisely 1,296,573.12.

- Standardization can work as a simplification control strategy if variety facing the organization is known and limited. But, it will not work in the face of unknown situations, i.e. where the variety in the environment exceeds the variety that the standardized tools allow.

- There are surely many more.

Simplification errors

- Trivialization is a family of errors (errors of omission, errors of representativeness, etc.) that arise when we try to ignore some of the environment’s variety. If we create a proof of concept based on a few examples, we can expect that the system won’t work, unless we have ensured that the examples are representative. A useful technique to avoid this error is simply gathering lists and categorizing their elements (ensuring that the categories are properly exclusive).

- Assuming the complexity won’t apply. As we saw above, complex situations contain unknowable elements. As a rule of thumb, we should assume a complex situation until we have solid knowledge that it is only complicated. Often trying to model the future system is sufficient to expose the unknown areas. Models are filters that absorb variety and make our decision areas explicit.

- “Let’s just get started”. The pressure of the project plan can lead the team to hurry into the work before we achieved sufficient understanding of the conceptual domain. Readers of these pages will note that we are committed to agile principles. But, there is a difference between enough-design-up-front and rushing in with the naïve belief that the difficulties will be worked out easily as we go along.

- As above, there are surely many more.

It cannot be stressed enough that “keeping it simple” is often harder conceptually than diving down the rabbit hole of details. It requires experience with the problem domains to recognize what is important. It requires tested heuristics to ensure completeness of scope. And, it requires hypothesis testing as a tool to uncover unwarranted assumptions early on. But, with a little discipline and a little practice, such techniques are neither hard nor costly.

Notes

- /1/ W. Ross Ashby (1903-1972) was a founding father of cybernetics and made major contributions to general systems theory in the middle of the twentieth century. W. Ross Ashby, Introduction to Cybernetics, London, Chapman & Hall, 1957. Several of Ashby’s key works are available at: http://rossashby.info/index.html. A useful summary of Ashby’s law may be found at: https://www.businessballs.com/strategy-innovation/ashbys-law-of-requisite-variety/

- /2/ Mark Lambertz https://leanbase.de/publishing/leanmagazin/uber-todliche-unterkomplexitat

Kommentare

Kommentar veröffentlichen